By Rev. Chris Jorgensen

June 14, 2020

Video of whole service: https://www.facebook.com/hanscomparkchurch/videos/724738988278570/

Scripture: Matthew 27:55-61

In today’s sermon on mental health, I do want to let you know that we are going to talk about suicidal ideation, self-harm, and violence in this sermon. I wanted to let you know that so you can take care of yourselves and your families in this moment.

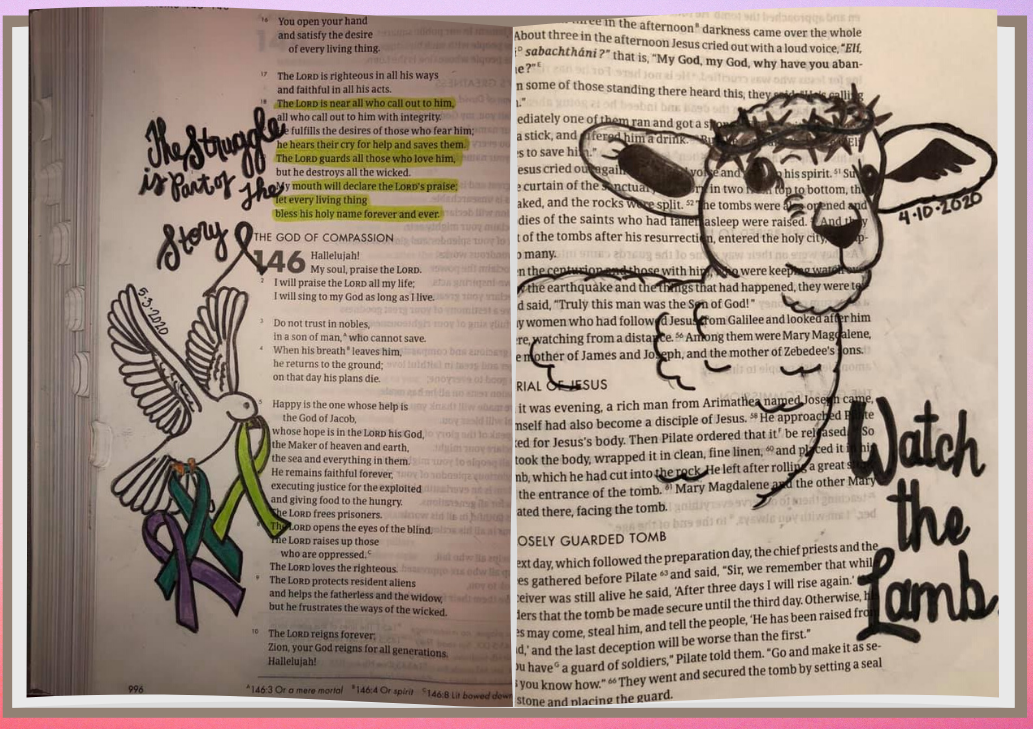

Like last week, today’s sermon is inspired by two of Lindsey Madsen’s drawings. The drawings include two phrases: “The Struggle is Part of the Story” and “Watch the Lamb.” The struggle drawing with the dove and the ribbons was drawn in May during Mental Health Awareness Month. Lindsey wrote this on Facebook about the drawing: “May is Mental Health Awareness Month. As a school counselor and advocate, I can say this is important until I’m blue in the face. Mental Health is just as important as physical health.”

I agree with Lindsey. We need to talk about this over and over. It is so important. We have of course talked about this in the past. We talked about mental health last May, we had Mental Health First Aid training last April, and we think of the work we do in our church garden as a way to encourage mental health. It might especially important to talk about it now – during these coronatimes, when maintaining mental health has become even more difficult.

The coronatimes has brought a sense of near-constant fear and anxiety. It’s brought a disruption of routines which help people to maintain mental health. It’s caused us to physically distance from our support systems for fear of contracting the virus. It’s made it more difficult for folks to go out and get needed medications or have doctor’s visits. Even the lack of hugs has made mental wellness more difficult to achieve for many of us.

Even in the beforetimes, mental illness was prevalent in our nation. You may have heard the statistics. “1 in 5 U.S. adults experience mental illness each year. 1 in 6 U.S. youth aged 6-17 experience a mental health disorder” according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness. That’s a lot of us. That means, in summary, that we…we as a church community, we are people who experience mental illness, and we know and love people who experience mental illness.

Our second image today – the lamb drawn on the scripture from the Gospel of Matthew – it has really got me thinking about our role in being present in solidarity and love with all people who experience mental illness.

This story starts right after Jesus died on the cross. Now hear this – and I am just telling the story. In every gospel, by the time Jesus is on the cross, the male disciples have run away. They are not there in his most difficult hour. The men have abandoned him. But not the women. As our scripture begins today, Jesus is on the cross, and the women are there looking on from a distance. They are watching the lamb. They are keeping their eyes and hearts on Jesus – who we sometimes call the Lamb of God. They are standing in solidarity with the one they love even when they cannot do one thing to stop what is happening to him. They do not abandon him.

When he dies, Joseph of Arimathea shows up. The text says he is a rich man. It is safe for him to be there because he is a rich man. He is an insider with power and privilege, and he uses that power and privilege to show up and give Jesus a proper burial. When the scene ends, the women are still there. They are still watching the lamb even when others have gone home afraid, even when others have gone home and given up all hope. These women – in their heartbreaking grief and pain – are keeping their eyes Jesus, their eyes on God. They knew that even though all seemed lost, God was with them still.

This reminded me of my experience of being the mother of a daughter with mental illness. Let me tell you the story. In some ways, it is not my story but my daughter Ruby’s story told from my perspective. So I want you to know that I asked her for permission and had her read this beforehand. She agreed – not surprisingly – because she is not ashamed, nor should she be ashamed – nor should anyone be ashamed of their struggles with mental health.

It’s a long story, a long journey. But I want to start with one particular memory of mine from January 2019. It is early in the morning. I am sitting at my dining room table. I have coffee and my prayer book and my journal laid out in front of me. But unlike every other morning, something about this morning is different. My 14-year-old daughter is not in the house. She is not in the house because the day before, my partner Matt and I, along with a nurse and safety officer walked with her to the fourth floor of Immanuel Hospital for her to be admitted to their in-patient behavioral health program. After years struggling with depression, anxiety, and OCD, even though she had counselors and medications, she had reached a breaking point. She had been self-harming and was suicidal. It wasn’t safe to have her in our home – even with all the medications and sharp objects locked away. So we brought her to the hospital, putting her in the care of people we didn’t know….and then we left and went home.

I don’t think I can explain how terrifying and heartbreaking that is. I recognize that my heartbreak, too, was nothing compared to Ruby’s.

I sat there, that morning at that table, and wept with terror. And also with profound gratitude.

Yes, gratitude.

That’s where I sensed God’s presence the most in the midst of this journey was in the gratitude. It seems almost miraculous looking back that any gratitude would bubble up for me in such a situation. But the gratitude that came was a potent reminder of what I believe to be unshakably true: that through all of it, God was always with me and, more importantly, God was always with Ruby.

So I sensed God’s presence in this gratitude. I was devastatingly grateful for every kindness in those days.

- I was grateful for people who listened without trying to give me answers – because those who offered “easy” answers made me feel like I was a terrible parent for not having already solved this complex medical, social, and emotional situation.

- I was grateful for kind and wise doctors and nurses and therapists. I was grateful to be in a place where in-patient behavioral health was available…and that we didn’t have to drop Ruby off somewhere hours away.

- I was grateful for Matt and I having jobs where we could have time off without getting fired. I actually didn’t go to a required clergy event – something I never would have missed for any other reason – and I was grateful for Bishop Saenz and my District Superintendent Chad Anglemyer for supporting me and praying for Ruby.

- I was grateful for health insurance – and having the savings to pay the big deductibles when those came through (even with our “great” health insurance – I mean it’s about as good as it gets…and yet still the out-of-pocket costs are significant.)

- I was grateful that we were treated with care and respect by everyone we encountered – which is certainly – at least partially – a function of our privilege as educated, middle class, white people.

And because of all those advantages, we made it through a truly difficult struggle that included another stint in the hospital a few weeks later and then weeks upon weeks of a full-time outpatient program, and Ruby missing basically half of her eighth-grade year in school.

But, but! Because of all those advantages, I am happy to report that Ruby is doing great now. She is still in therapy and still take medication. And she is happy. She has all kinds of friends – including those in our church youth group. She is excited about life. She is thinking about her future. She even applied for a job this past Friday. Fingers crossed!

I am grateful.

But as a Christian, I can’t just be glad I had all of those privileges and advantages when I know so many people do not. Many people struggle when trying to access mental health care. The barriers to access to care are many and various: high cost of care and insufficient insurance coverage, limited options and long waits to see caregivers (friends, we NEED more psychiatrists!), lack of awareness to where to even start accessing care, and finally social stigma that prevents people from reaching out when they need help. [Source: https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/press-releases/new-study-reveals-lack-of-access-as-root-cause-for-mental-health-crisis-in-america/]

ALL of these barriers to accessing mental health care affect people of color more than white people; yet, we hardly even talk about that. In fact, I recently learned that July is Minority Mental Health Month. I didn’t even know that was a thing. Now that I know, I can do better. In fact, I’ve recently started educating myself about the effects of racism and racial disparities on the mental health of people and communities of color. The United Church of Christ Mental Health Network recently put out a statement about this very topic. I read it, listening carefully to hear what I have overlooked in the past. Here is what they wrote:

“We agree with the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) along with the numerous doctors and public health professional organizations that have declared racism to be a public health crisis. NAMI has published a statement saying, “The effect of racism and racial trauma on mental health is real and cannot be ignored. The disparity in access to mental health care in communities of color cannot be ignored. The inequality and lack of cultural competency in mental health treatment cannot be ignored.”

In addition, [we align] ourselves with our thirtieth UCC General Synod…It “identifies mass incarceration as a critical human and civil rights issue in the U.S. because of its disparate impact on and disenfranchisement of people of color, youth, people with mental illness, and people with limited economic and other resources.” The reality is that at least 1/3 of all persons who are in jail have mental health conditions.”

I’m going to repeat that: at least one-third of all persons who are in jail have mental health conditions.

The letter goes on to say, “We raise the call to require police officers to be trained about how to interact with people who have mental health issues. When ignorance about mental illness combines with racism it creates a double injustice.

Such pain and agony cry out for healing. … Such reality has been lived by people of color for generations. Now is the time to acknowledge that reality, to repent for its tenacious grip on us all, and collectively act our way into a new way of being.”

As a mother of a child with mental illness, I hear this as my call to stand in solidarity with all mothers of children with mental illness, and to especially stand with black and brown mothers: mothers whose children deserve healing and help just as much as mine. I hear this as my call to stand with those mothers who don’t have health insurance and don’t know where to turn. I hear this as my call to stand with mothers who, because of the color of their – or their children’s – skin will be dismissed or criminalized rather than supported and treated. I hear this as my call to stand with Zachary BearHeels’s mother Renita, whose mentally ill son died at the hands of the police – rather than being treated with the tender care afforded to a 14-year-old white girl.

All of our children should be afforded such tender care. We should all be afforded such tender care. I know that God holds each of us with such care – and I will not walk away until all people are treated as God’s children. Like those women at the tomb, I will not desert my friends, my family, or any person in our community – not just the white community, but our WHOLE community. I will not desert the people I love, the people God loves, the people who experience mental illness, in their darkest hour.

So I will stand outside the tomb until we see the day when mental health services are fully funded and fully staffed.

I will stand outside the tomb until we see the day when mental health services are equally available to all people.

I will stand outside the tomb until all people experiencing mental illness are treated the way my daughter was treated: with love and tenderness and mercy.

I will stand outside the tomb until we see some resurrection.

I hope you will stand with me.

May it be so.

Amen.